Posts Tagged classroom-culture

Expanding what counts as good at science: Strategies for helping students value a wide range of skills in science

Posted by Marta R. Stoeckel in Uncategorized on July 9, 2025

This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in The Science Teacher on July 7, 20225, available at https://doi.org/10.1080/00368555.2024.2404955

The Next Generation Science Standards call for students to go beyond recalling answers and use a broad range of skills described in the science and engineering practices (NGSS Lead States, 2013). Yet, many students have a narrow view of what it means to be good at science, especially physics, seeing it as quickly getting to the answers and discounting the skills it takes to figure answers out (Archer et al., 2020). Students are also more likely to study science or closely related fields when they see themselves as good at science (Avraamidou, 2020). When students have a narrow view of what it means to be good at science, they are less likely to see the ways they are good at it, which is one factor in equity issues in science. One of the ways students come to understand what it means to be good at science and whether they are good at science is by watching what their peers give and receive recognition for, but there has not been much research on what recognition between students looks like (Kim & Sinatra, 2018). To get a better understanding of how students recognize each other, I used classroom video and student interviews to examine what kinds of contributions students recognized and how recognition fits with students’ sense of how they were good at science. Through reflective conversations with the teacher, I also considered how the teacher’s decisions impacted students’ sense of what it meant to be good at science. In this article, I will focus on findings about what students thought it meant to be good at science in their classroom and reflections from the teacher on what may have contributed to their view and how she changed her practice as a result of this study.

The Study

I collected data in AP Physics 1 at a large suburban public school. The class had 11 students in 11th and 12th grade and used a curriculum adapted from Modeling Instruction (Jackson et al., 2008), an approach that emphasizes guided inquiry and student-to-student discussion. Each unit begins with a paradigm lab, where students are introduced to a phenomenon, then collaboratively design experiments and share their results in whole-class discussions to develop an initial model. The rest of the unit is dedicated to refining and applying the model using a variety of activities designed to encourage student-to-student discourse among both small groups and the whole class. Over eight 55 minute class periods in March and April, I recorded video of small groups to look for moments where one student gave another recognition. At this point in the year, students had well-established relationships with their peers and worked in self-selected groups on a variety of activities including a paradigm lab, a card sort, a lab practical, and collaborative problem-solving. A few weeks after the videos were recorded, I also interviewed students about peer recognition, what they thought it means to be good at science, and how they saw themselves as good at science.

I collaborated with another researcher to identify and categorize examples of recognition in the small group videos and compare the recognition we saw to what students described in interviews. I identified two main categories of recognition, explicit and implicit, mirroring the ways teachers recognize students (Wang & Hazari, 2018). Explicit recognition described cases where one student gave another direct recognition, such as stating they believed a peer’s answer was correct or directing a question to a particular peer. Implicit recognition described cases that were more subtle, such as when students would build on or refine an idea shared by a peer or respond to a question asked by a peer with a rich discussion. Explicit recognition usually happened when students thought a statement or idea was correct. Implicit recognition happened in response to a much wider range of contributions, including asking good questions or sharing an idea that might incomplete or incorrect. Throughout the analysis, I regularly shared my progress with the classroom teacher. The teacher used this as an opportunity to reflect on how her choices and the intentions behind them fit with my findings, as well as what she was doing differently in her classroom as a result of this study.

What Does It Mean to Be Good At Science?

When I asked the students about what it means to be good at science in general or the ways their peers are good at science, students talked about a range of skills and contributions. While they valued things like being able to get the right answer or figure out the next step in a process, they saw that as only one component of being good at science. In particular, many students said being good at science requires asking questions. As one student put it, “Questions is probably the most important thing. Whether it’s a question for understanding or a question to see if we’re doing this right or even just offering another way to do something. I’d say that’s the most important thing.” Students also thought that being good at science meant being willing to share ideas, including ones that are incomplete or even wrong. As one student put it, “I think like sharing out ideas to each other even though it might not work.” Students not only described these kinds of skills as important but talked about how specific peers had demonstrated those skills. When they described giving their classmates recognition for things like asking questions or sharing ideas, they mostly talked about giving implicit recognition. Teachers have a lot of power to shape what strengths students see as important (Louie, 2018), so the choices of the teacher, summarized in Table 1. likely influenced the broad view these students had of what it means to be good at science.

Table 1: Strategies for Expanding What Counts as Good at Science

| Ways to be Good at Science | Strategy |

| Asking questions | Use sentence stems for student discussions that encourage students to ask questions, like those in Figure 1 (Wildeboer, n.d.) |

| Asking questions | Give students explicit recognition for questions, like “Great question!” or “Thank you for asking that.” |

| Asking questions | During student discussions, take notes on students who asked questions that led to productive discussion and publicly acknowledge them after |

| Sharing ideas and making mistakes | Go over problems by having groups prepare a whiteboard of a problem with an intentional mistake, like the one in Figure 2, then challenge the rest of the class to find and correct the mistake (O’Shea, 2012) |

| A range of skills | After an activity, have the class brainstorm a list of skills and abilities their group used and how they used them, like the list in Figure 3 (Cohen & Lotan, 2014) |

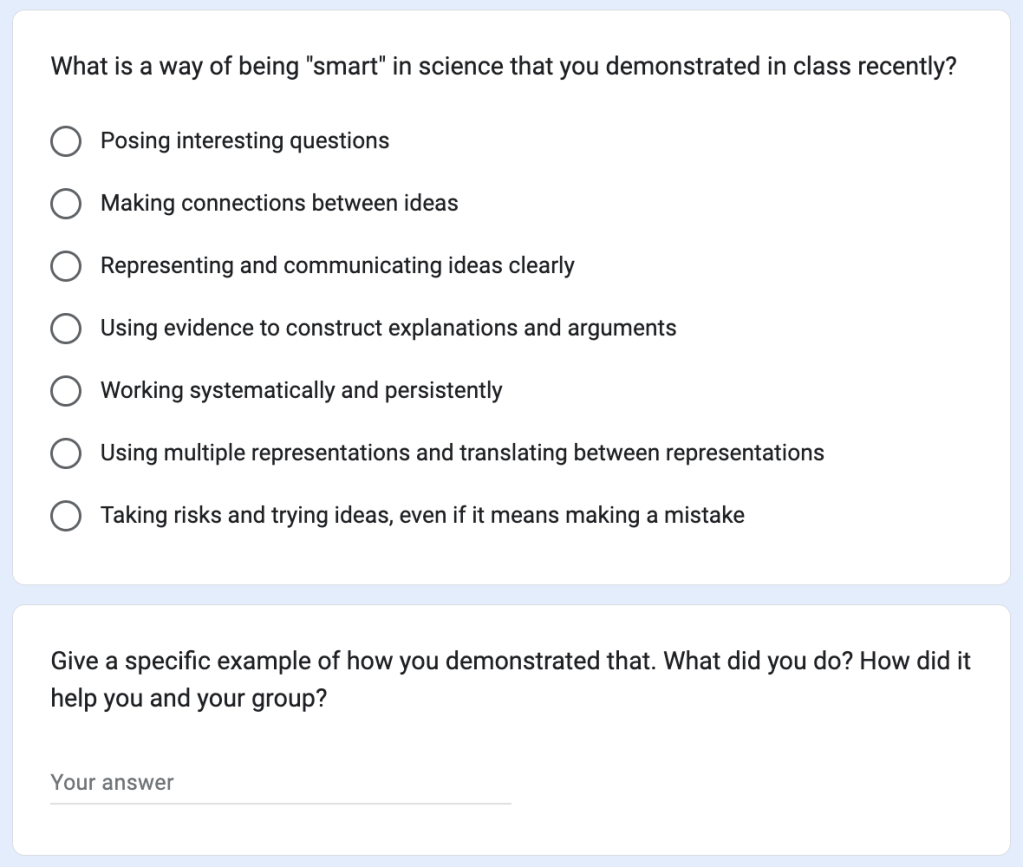

| A range of skills | Have students complete individual reflections like the one in Figure 4 that explicitly highlights broad ways of being good at science (O’Shea, 2016) |

Strategies for Valuing Questions

The teacher was excited by the value students placed on questions because she had been using several moves with the goal of promoting that view. For whole-class discussions, the teacher gave students the sentence stems shown in Figure 1 (Wildeboer, n.d.). Almost all the stems were questions, which the teacher explained to students was intentional because good questions would help their peers clarify their thinking and refine their ideas, leading to more learning for everyone in the room. She frequently reminded students of this to try and communicate to students how valuable questions are. The teacher also told students that the best questions were ones the asker didn’t know the answer to with the goal of showing students they could make a meaningful contribution even when they were confused.

Figure 1: A set of sentence stems posted in the classroom (Wildeboer, n.d.). These helped show asking questions is a valuable way to contribute to a discussion.

The teacher realized explicit recognition described another strategy she used to help students value questions. She had been making a point to consciously celebrate student questions. When delivering whole-class instruction or working with small groups, the teacher worked to immediately thank students for their questions or give praise like “Great question!” During whole-class discussions or other activities where she did not want to interrupt student-to-student conversations, the teacher took notes on questions that had led to particularly productive discussion or otherwise helped move the class forward so she could publicly acknowledge students who had asked productive questions later. Several students shared with the teacher that the explicit recognition she gave helped them feel like she valued their questions, which made them feel comfortable asking questions. As a result, these students said they asked more questions in physics than in their other classes. This gave students lots of opportunities to see how the questions they and their peers asked could help their learning, likely contributing to the clear value students placed on questions in the interviews.

Strategies for Valuing Mistakes

The teacher also made a conscious effort to value student ideas, even when they were incomplete or incorrect. She considered her most important move going over problems using “mistakes whiteboarding” (O’Shea, 2012), rather than presenting answers herself. Each group prepared a whiteboard with their solution to a problem, but included at least one intentional mistake, such as in the whiteboard in Figure 2. Groups then presented their whiteboard to the rest of the class, who had to find and correct the mistake. The teacher found this activity helped students think deeply about the problems, both as they tried to come up with good mistakes and as they figured out how to correct the mistakes their peers presented. Students often reported to the teacher that mistakes whiteboarding was one of the most useful activities in helping them understand the content and even celebrated when they made a mistake on a problem because that meant they could use it for whiteboarding. This activity framed mistakes and wrong answers as an important resource for learning, which likely contributed to the value students placed on sharing ideas.

Figure 2: A whiteboard showing different representations of the same motion with an intentional mistake in the position vs. time graph. By having students present intentional mistakes, the teacher was able to show mistakes and wrong answers were a useful resource for learning.

Strategies for Valuing Other Contributions

Another goal of the teacher was to show students the value of collaboration by making sure they saw the breadth of skills needed for many of the activities in a science classroom. Early in the school year, after students completed selected activities, she asked students to brainstorm the skills their group needed to complete the activity, which she then recorded during a whole-class discussion (Cohen & Lotan, 2014), generating a list of skills like the one in Figure 3. Students usually generated an expansive list that included skills like sketching ideas or diagrams, analyzing data, and clearly communicating. The skills students identified usually had significant overlap with the NGSS science practices (NGSS Lead States, 2013), but were also diverse enough that every student could identify at least one skill or ability that they believed they were good at. The teacher also asked students how their group had needed each skill or ability to ensure that students were seeing the skills and abilities they listed as substantive contributions to their group and necessary to doing the science.

Figure 3: A list of skills students said their group needed for a lab to graph the motion of a buggy moving at a constant velocity. This list helped students see the range of skills their group needed.

The teacher also used individual reflections to help students develop a broad view of what it means to be good at science. To communicate her own view, she used the reflection in Figure 4 that listed general ways of being “smart” in science that included items like posing interesting questions, representing and communicating ideas clearly, and making connections between ideas (O’Shea, 2016). Students then described a specific way they had used one those abilities in their science class recently, giving themselves explicit recognition for something beyond just finding the right answer. In interviews, the skills students associated with being good at science overlapped with the skills on this reflection, indicating they had a broad view that aligned with the reflection.

Figure 4: A survey based on O’Shea (2016) where students reflected on their contributions in class. This reflection helped students think about a wide range of ways of being good at science.

How Am I Good at Science?

Students talked about the ways they personally were good at science very differently than they talked about their peers. They described their most important contributions to the group as having the answers or knowing how to get them. As one student put it, “It’s knowing what specifically to look for when encountering a problem. Knowing the exact model and how to apply it, really knowing what you need for the problem.” One of the students who described asking questions as an important way his classmates were good at science even described himself as bad at science because “I tend to ask a lot of questions”. The narrow ways of being good at science that students saw in themselves fit very well with the kinds of contributions that led to explicit recognition when they worked in small groups. This made it unsurprising that when students described recognition they had received from peers, they mostly described explicit recognition. This suggests that explicit recognition from peers played an important role in how students came to see themselves as good at science.

When I shared this finding with the teacher, she was disappointed that students applied such a narrow view of what it means to be good at science to themselves. She was especially concerned given the equity implications of this finding. For example, other studies have found boys are more likely than girls to present ideas and suggestions to their groups and to use their contributions to show off their competence in science (Wieselmann et al., 2019), the same kinds of contributions that tended to receive explicit recognition from other students in this study. Girls, meanwhile, tended to use their contributions to seek a deeper understanding of the material and of their peer’s ideas (Wieselmann et al., 2019), which students in this study saw as important but tended to mostly acknowledge with more subtle implicit recognition. If these patterns were also present in this classroom, they could easily lead to boys getting more explicit recognition from peers. Especially because one reason that women do not persist in physics is they tend to report receiving less recognition than men (Kalender et al., 2019), the teacher responded to these findings by looking for ways she could help students give each other explicit recognition for the broad range of contributions she wanted students to value in her classroom.

When discussing my findings, the teacher noted that students likely gave most of their explicit recognition for things like correct answers because it was immediately clear to students how that contribution could move the group forward. Other contributions, like a good question, often take time to lead to something that moves the group forward in a concrete way. It takes a lot of attention for students to realize how a particular question that may have been asked several minutes ago helped the group progress, then to think of saying something to the person who asked the question when they are trying to think through the science at the same time. However, in the reflective setting of the interviews, students were able to recognize very specific ways their peers demonstrated skills beyond getting correct answers. In fact, had the teacher and I shared the interview transcripts with the students who were described, the interviews would easily have served as explicit recognition for a wide range of skills. Since reflection was already a part of the teacher’s practice, she decided to incorporate explicit recognition into the reflections she asked her students to do. These strategies are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Strategies for Reflective Recognition

| Strategy |

| After an activity, have students complete a reflection like the one in Figure 5 where they describe how a member of their group demonstrated a skill or ability from a list generated by the class of what they needed to complete the ability, such as the list in Figure 3 |

| Have students complete a reflection like the one in Figure 6 that asks students to describe how a member of their group demonstrated one of several broad ways of being good at science and how it helped their learning |

Strategies for Reflective Recognition

For the first strategy, the teacher built on the discussions where students brainstormed the skills needed for a task, such as the one in Figure 3. Once the class generated a list of skills required for a particular task, each student was assigned another member of their group. She used a variety of random strategies, such as numbering students within each group, to ensure that every student in the class had someone assigned to them. Students then completed the reflection in Figure 5 where they identified a particular skill off the list their class had brainstormed and wrote about how the they person they were assigned had used that skill during the activity. After reviewing the reflections, the teacher then gave each student the reflection about them, ensuring that every student received explicit recognition from a peer. Since the list brainstormed by the class rarely included simply knowing the answer, this recognition was usually for the broad ways of being good at science the teacher wanted to encourage. For the second strategy, the teacher made a similar modification to the reflection in Figure 4 (O’Shea, 2016) that listed ways of being “smart” in science. She asked students to reflect on how their recent group members had demonstrated one of the skills and describe a specific instance where a group member had demonstrated one of the skills, including how it helped the writer’s learning using the reflection in Figure 6. The teacher collected these reflections until she had some about each student, then shared them with the students who had been written about. Similar to the reflections based on the brainstormed list, by asking students to focus on the list of skills she provided, the teacher was able to ensure students gave each other explicit recognition for broader kinds of skills than the contributions like correct answers that students spontaneously recognized each other for in the study. With both these reflections, the teacher found students took these reflections very seriously knowing their classmates would read them and that several students had shared with her they hadn’t realized they were good at some skill until they saw their classmate’s reflections.

Figure 5: A survey where students reflected on how someone from their group demonstrated a skill from a list of skills the group needed to complete a lesson, such as the list in Figure 3. The teacher used these surveys to ensure students got explicit recognition for something besides having correct answers.

Figure 6: A survey based on O’Shea (2016) where students reflected on a peer’s contributions to their group. The teacher used these surveys to ensure students got explicit recognition for something besides having correct answers.

Conclusion

Helping students understand that science is not just about right answers and requires a wide range of skills is key to the reforms in the NGSS. Aided by the teacher’s efforts, students recognized many ways to be good at science and saw the ways their peers demonstrated those skills. When it came to ways they personally were good at science, students had a much more limited view that was connected to what their peers gave explicit recognition for. In a reflective setting, students could give recognition for contributions that were difficult to explicitly recognize in the moment. Finding ways for students to give each other recognition reflectively is an important step in ensuring that students not only see that being good at science involves a range of skills, but that they have those skills.

References

Archer, L., Moote, J., & MacLeod, E. (2020). Learning that physics is ‘not for me’: Pedagogic work and the cultivation of habitus among advanced level physics students. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 29(3), 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2019.1707679

Avraamidou, L. (2020). Science identity as a landscape of becoming: Rethinking recognition and emotions through an intersectionality lens. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 15(2), 323–345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-019-09954-7

Cohen, E. G., & Lotan, R. A. (2014). Designing Groupwork: Strategies for the Heterogenous Classroom (3rd ed.). Teachers College Press.

Jackson, J., Dukerich, L., & Hestenes, D. (2008). Modeling Instruction: An effective model for science education. Science Educator, 17(1), 10–17. http://modeling.asu.edu

Kalender, Z. Y., Marshman, E., Schunn, C. D., Nokes-Malach, T. J., & Singh, C. (2019). Why female science, technology, engineering, and mathematics majors do not identify with physics: They do not think others see them that way. Physical Review Physics Education Research, 15(2), 020148. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevPhysEducRes.15.020148

Kim, A. Y., & Sinatra, G. M. (2018). Science identity development: an interactionist approach. International Journal of STEM Education, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-018-0149-9

Louie, N. L. (2018). Culture and ideology in mathematics teacher noticing. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 97(1), 55–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-017-9775-2

NGSS Lead States. (2013). Next Generation Science Standards.

O’Shea, K. (2012). Whiteboarding mistakes game: A guide. Physics! Blog!

O’Shea, K. (2016). Being “smart” in science class. Plysics! Blog! https://kellyoshea.blog/2016/11/08/being-smart-in-science-class/

Wang, J., & Hazari, Z. (2018). Promoting high school students’ physics identity through explicit and implicit recognition. Physical Review Physics Education Research, 14(2). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevPhysEducRes.14.020111

Wieselmann, J. R., Dare, E. A., Ring-Whalen, E. A., & Roehrig, G. H. (2019). “I just do what the boys tell me”: Exploring small group student interactions in an integrated STEM unit. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 57(1), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21587

Wildeboer, B. (n.d.). Student discourse question stems. Retrieved December 11, 2024, from https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1Wml9a25NV1Qv-73RnK_zLKE1zG3RQaJgsBX2UMf7XYc/edit#slide=id.p