Archive for category Uncategorized

Expanding what counts as good at science: Strategies for helping students value a wide range of skills in science

Posted by Marta R. Stoeckel in Uncategorized on July 9, 2025

This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in The Science Teacher on July 7, 20225, available at https://doi.org/10.1080/00368555.2024.2404955

The Next Generation Science Standards call for students to go beyond recalling answers and use a broad range of skills described in the science and engineering practices (NGSS Lead States, 2013). Yet, many students have a narrow view of what it means to be good at science, especially physics, seeing it as quickly getting to the answers and discounting the skills it takes to figure answers out (Archer et al., 2020). Students are also more likely to study science or closely related fields when they see themselves as good at science (Avraamidou, 2020). When students have a narrow view of what it means to be good at science, they are less likely to see the ways they are good at it, which is one factor in equity issues in science. One of the ways students come to understand what it means to be good at science and whether they are good at science is by watching what their peers give and receive recognition for, but there has not been much research on what recognition between students looks like (Kim & Sinatra, 2018). To get a better understanding of how students recognize each other, I used classroom video and student interviews to examine what kinds of contributions students recognized and how recognition fits with students’ sense of how they were good at science. Through reflective conversations with the teacher, I also considered how the teacher’s decisions impacted students’ sense of what it meant to be good at science. In this article, I will focus on findings about what students thought it meant to be good at science in their classroom and reflections from the teacher on what may have contributed to their view and how she changed her practice as a result of this study.

The Study

I collected data in AP Physics 1 at a large suburban public school. The class had 11 students in 11th and 12th grade and used a curriculum adapted from Modeling Instruction (Jackson et al., 2008), an approach that emphasizes guided inquiry and student-to-student discussion. Each unit begins with a paradigm lab, where students are introduced to a phenomenon, then collaboratively design experiments and share their results in whole-class discussions to develop an initial model. The rest of the unit is dedicated to refining and applying the model using a variety of activities designed to encourage student-to-student discourse among both small groups and the whole class. Over eight 55 minute class periods in March and April, I recorded video of small groups to look for moments where one student gave another recognition. At this point in the year, students had well-established relationships with their peers and worked in self-selected groups on a variety of activities including a paradigm lab, a card sort, a lab practical, and collaborative problem-solving. A few weeks after the videos were recorded, I also interviewed students about peer recognition, what they thought it means to be good at science, and how they saw themselves as good at science.

I collaborated with another researcher to identify and categorize examples of recognition in the small group videos and compare the recognition we saw to what students described in interviews. I identified two main categories of recognition, explicit and implicit, mirroring the ways teachers recognize students (Wang & Hazari, 2018). Explicit recognition described cases where one student gave another direct recognition, such as stating they believed a peer’s answer was correct or directing a question to a particular peer. Implicit recognition described cases that were more subtle, such as when students would build on or refine an idea shared by a peer or respond to a question asked by a peer with a rich discussion. Explicit recognition usually happened when students thought a statement or idea was correct. Implicit recognition happened in response to a much wider range of contributions, including asking good questions or sharing an idea that might incomplete or incorrect. Throughout the analysis, I regularly shared my progress with the classroom teacher. The teacher used this as an opportunity to reflect on how her choices and the intentions behind them fit with my findings, as well as what she was doing differently in her classroom as a result of this study.

What Does It Mean to Be Good At Science?

When I asked the students about what it means to be good at science in general or the ways their peers are good at science, students talked about a range of skills and contributions. While they valued things like being able to get the right answer or figure out the next step in a process, they saw that as only one component of being good at science. In particular, many students said being good at science requires asking questions. As one student put it, “Questions is probably the most important thing. Whether it’s a question for understanding or a question to see if we’re doing this right or even just offering another way to do something. I’d say that’s the most important thing.” Students also thought that being good at science meant being willing to share ideas, including ones that are incomplete or even wrong. As one student put it, “I think like sharing out ideas to each other even though it might not work.” Students not only described these kinds of skills as important but talked about how specific peers had demonstrated those skills. When they described giving their classmates recognition for things like asking questions or sharing ideas, they mostly talked about giving implicit recognition. Teachers have a lot of power to shape what strengths students see as important (Louie, 2018), so the choices of the teacher, summarized in Table 1. likely influenced the broad view these students had of what it means to be good at science.

Table 1: Strategies for Expanding What Counts as Good at Science

| Ways to be Good at Science | Strategy |

| Asking questions | Use sentence stems for student discussions that encourage students to ask questions, like those in Figure 1 (Wildeboer, n.d.) |

| Asking questions | Give students explicit recognition for questions, like “Great question!” or “Thank you for asking that.” |

| Asking questions | During student discussions, take notes on students who asked questions that led to productive discussion and publicly acknowledge them after |

| Sharing ideas and making mistakes | Go over problems by having groups prepare a whiteboard of a problem with an intentional mistake, like the one in Figure 2, then challenge the rest of the class to find and correct the mistake (O’Shea, 2012) |

| A range of skills | After an activity, have the class brainstorm a list of skills and abilities their group used and how they used them, like the list in Figure 3 (Cohen & Lotan, 2014) |

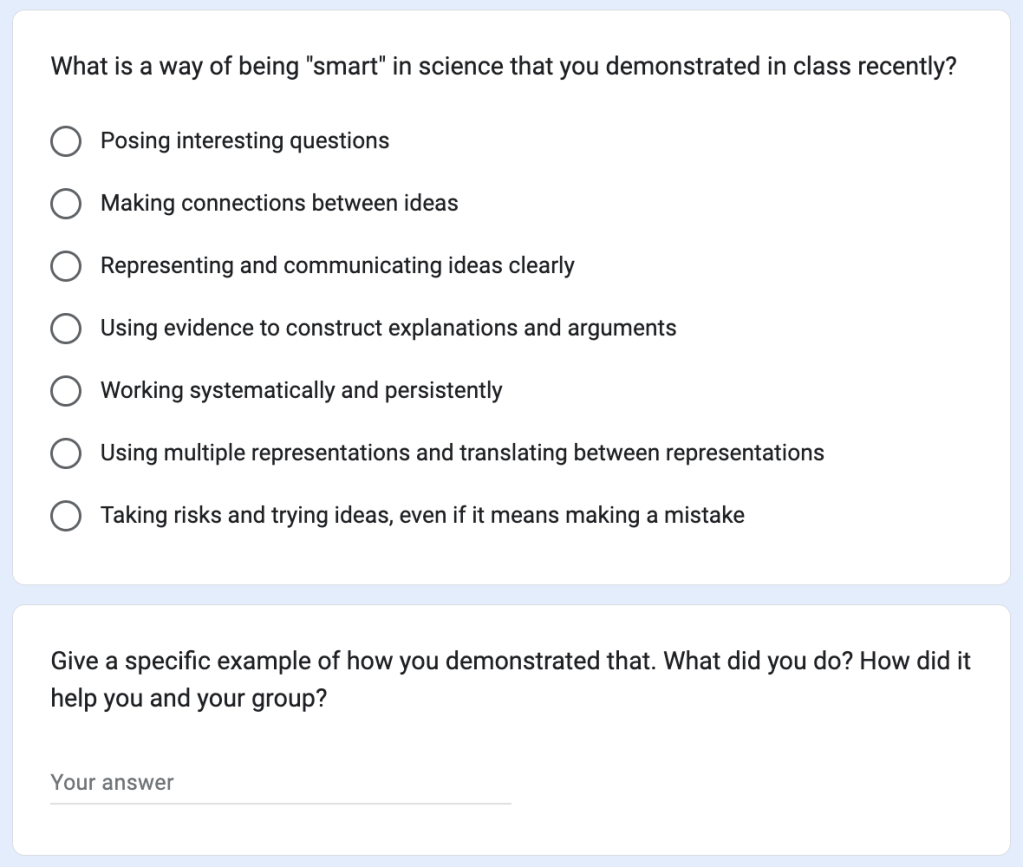

| A range of skills | Have students complete individual reflections like the one in Figure 4 that explicitly highlights broad ways of being good at science (O’Shea, 2016) |

Strategies for Valuing Questions

The teacher was excited by the value students placed on questions because she had been using several moves with the goal of promoting that view. For whole-class discussions, the teacher gave students the sentence stems shown in Figure 1 (Wildeboer, n.d.). Almost all the stems were questions, which the teacher explained to students was intentional because good questions would help their peers clarify their thinking and refine their ideas, leading to more learning for everyone in the room. She frequently reminded students of this to try and communicate to students how valuable questions are. The teacher also told students that the best questions were ones the asker didn’t know the answer to with the goal of showing students they could make a meaningful contribution even when they were confused.

Figure 1: A set of sentence stems posted in the classroom (Wildeboer, n.d.). These helped show asking questions is a valuable way to contribute to a discussion.

The teacher realized explicit recognition described another strategy she used to help students value questions. She had been making a point to consciously celebrate student questions. When delivering whole-class instruction or working with small groups, the teacher worked to immediately thank students for their questions or give praise like “Great question!” During whole-class discussions or other activities where she did not want to interrupt student-to-student conversations, the teacher took notes on questions that had led to particularly productive discussion or otherwise helped move the class forward so she could publicly acknowledge students who had asked productive questions later. Several students shared with the teacher that the explicit recognition she gave helped them feel like she valued their questions, which made them feel comfortable asking questions. As a result, these students said they asked more questions in physics than in their other classes. This gave students lots of opportunities to see how the questions they and their peers asked could help their learning, likely contributing to the clear value students placed on questions in the interviews.

Strategies for Valuing Mistakes

The teacher also made a conscious effort to value student ideas, even when they were incomplete or incorrect. She considered her most important move going over problems using “mistakes whiteboarding” (O’Shea, 2012), rather than presenting answers herself. Each group prepared a whiteboard with their solution to a problem, but included at least one intentional mistake, such as in the whiteboard in Figure 2. Groups then presented their whiteboard to the rest of the class, who had to find and correct the mistake. The teacher found this activity helped students think deeply about the problems, both as they tried to come up with good mistakes and as they figured out how to correct the mistakes their peers presented. Students often reported to the teacher that mistakes whiteboarding was one of the most useful activities in helping them understand the content and even celebrated when they made a mistake on a problem because that meant they could use it for whiteboarding. This activity framed mistakes and wrong answers as an important resource for learning, which likely contributed to the value students placed on sharing ideas.

Figure 2: A whiteboard showing different representations of the same motion with an intentional mistake in the position vs. time graph. By having students present intentional mistakes, the teacher was able to show mistakes and wrong answers were a useful resource for learning.

Strategies for Valuing Other Contributions

Another goal of the teacher was to show students the value of collaboration by making sure they saw the breadth of skills needed for many of the activities in a science classroom. Early in the school year, after students completed selected activities, she asked students to brainstorm the skills their group needed to complete the activity, which she then recorded during a whole-class discussion (Cohen & Lotan, 2014), generating a list of skills like the one in Figure 3. Students usually generated an expansive list that included skills like sketching ideas or diagrams, analyzing data, and clearly communicating. The skills students identified usually had significant overlap with the NGSS science practices (NGSS Lead States, 2013), but were also diverse enough that every student could identify at least one skill or ability that they believed they were good at. The teacher also asked students how their group had needed each skill or ability to ensure that students were seeing the skills and abilities they listed as substantive contributions to their group and necessary to doing the science.

Figure 3: A list of skills students said their group needed for a lab to graph the motion of a buggy moving at a constant velocity. This list helped students see the range of skills their group needed.

The teacher also used individual reflections to help students develop a broad view of what it means to be good at science. To communicate her own view, she used the reflection in Figure 4 that listed general ways of being “smart” in science that included items like posing interesting questions, representing and communicating ideas clearly, and making connections between ideas (O’Shea, 2016). Students then described a specific way they had used one those abilities in their science class recently, giving themselves explicit recognition for something beyond just finding the right answer. In interviews, the skills students associated with being good at science overlapped with the skills on this reflection, indicating they had a broad view that aligned with the reflection.

Figure 4: A survey based on O’Shea (2016) where students reflected on their contributions in class. This reflection helped students think about a wide range of ways of being good at science.

How Am I Good at Science?

Students talked about the ways they personally were good at science very differently than they talked about their peers. They described their most important contributions to the group as having the answers or knowing how to get them. As one student put it, “It’s knowing what specifically to look for when encountering a problem. Knowing the exact model and how to apply it, really knowing what you need for the problem.” One of the students who described asking questions as an important way his classmates were good at science even described himself as bad at science because “I tend to ask a lot of questions”. The narrow ways of being good at science that students saw in themselves fit very well with the kinds of contributions that led to explicit recognition when they worked in small groups. This made it unsurprising that when students described recognition they had received from peers, they mostly described explicit recognition. This suggests that explicit recognition from peers played an important role in how students came to see themselves as good at science.

When I shared this finding with the teacher, she was disappointed that students applied such a narrow view of what it means to be good at science to themselves. She was especially concerned given the equity implications of this finding. For example, other studies have found boys are more likely than girls to present ideas and suggestions to their groups and to use their contributions to show off their competence in science (Wieselmann et al., 2019), the same kinds of contributions that tended to receive explicit recognition from other students in this study. Girls, meanwhile, tended to use their contributions to seek a deeper understanding of the material and of their peer’s ideas (Wieselmann et al., 2019), which students in this study saw as important but tended to mostly acknowledge with more subtle implicit recognition. If these patterns were also present in this classroom, they could easily lead to boys getting more explicit recognition from peers. Especially because one reason that women do not persist in physics is they tend to report receiving less recognition than men (Kalender et al., 2019), the teacher responded to these findings by looking for ways she could help students give each other explicit recognition for the broad range of contributions she wanted students to value in her classroom.

When discussing my findings, the teacher noted that students likely gave most of their explicit recognition for things like correct answers because it was immediately clear to students how that contribution could move the group forward. Other contributions, like a good question, often take time to lead to something that moves the group forward in a concrete way. It takes a lot of attention for students to realize how a particular question that may have been asked several minutes ago helped the group progress, then to think of saying something to the person who asked the question when they are trying to think through the science at the same time. However, in the reflective setting of the interviews, students were able to recognize very specific ways their peers demonstrated skills beyond getting correct answers. In fact, had the teacher and I shared the interview transcripts with the students who were described, the interviews would easily have served as explicit recognition for a wide range of skills. Since reflection was already a part of the teacher’s practice, she decided to incorporate explicit recognition into the reflections she asked her students to do. These strategies are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Strategies for Reflective Recognition

| Strategy |

| After an activity, have students complete a reflection like the one in Figure 5 where they describe how a member of their group demonstrated a skill or ability from a list generated by the class of what they needed to complete the ability, such as the list in Figure 3 |

| Have students complete a reflection like the one in Figure 6 that asks students to describe how a member of their group demonstrated one of several broad ways of being good at science and how it helped their learning |

Strategies for Reflective Recognition

For the first strategy, the teacher built on the discussions where students brainstormed the skills needed for a task, such as the one in Figure 3. Once the class generated a list of skills required for a particular task, each student was assigned another member of their group. She used a variety of random strategies, such as numbering students within each group, to ensure that every student in the class had someone assigned to them. Students then completed the reflection in Figure 5 where they identified a particular skill off the list their class had brainstormed and wrote about how the they person they were assigned had used that skill during the activity. After reviewing the reflections, the teacher then gave each student the reflection about them, ensuring that every student received explicit recognition from a peer. Since the list brainstormed by the class rarely included simply knowing the answer, this recognition was usually for the broad ways of being good at science the teacher wanted to encourage. For the second strategy, the teacher made a similar modification to the reflection in Figure 4 (O’Shea, 2016) that listed ways of being “smart” in science. She asked students to reflect on how their recent group members had demonstrated one of the skills and describe a specific instance where a group member had demonstrated one of the skills, including how it helped the writer’s learning using the reflection in Figure 6. The teacher collected these reflections until she had some about each student, then shared them with the students who had been written about. Similar to the reflections based on the brainstormed list, by asking students to focus on the list of skills she provided, the teacher was able to ensure students gave each other explicit recognition for broader kinds of skills than the contributions like correct answers that students spontaneously recognized each other for in the study. With both these reflections, the teacher found students took these reflections very seriously knowing their classmates would read them and that several students had shared with her they hadn’t realized they were good at some skill until they saw their classmate’s reflections.

Figure 5: A survey where students reflected on how someone from their group demonstrated a skill from a list of skills the group needed to complete a lesson, such as the list in Figure 3. The teacher used these surveys to ensure students got explicit recognition for something besides having correct answers.

Figure 6: A survey based on O’Shea (2016) where students reflected on a peer’s contributions to their group. The teacher used these surveys to ensure students got explicit recognition for something besides having correct answers.

Conclusion

Helping students understand that science is not just about right answers and requires a wide range of skills is key to the reforms in the NGSS. Aided by the teacher’s efforts, students recognized many ways to be good at science and saw the ways their peers demonstrated those skills. When it came to ways they personally were good at science, students had a much more limited view that was connected to what their peers gave explicit recognition for. In a reflective setting, students could give recognition for contributions that were difficult to explicitly recognize in the moment. Finding ways for students to give each other recognition reflectively is an important step in ensuring that students not only see that being good at science involves a range of skills, but that they have those skills.

References

Archer, L., Moote, J., & MacLeod, E. (2020). Learning that physics is ‘not for me’: Pedagogic work and the cultivation of habitus among advanced level physics students. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 29(3), 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2019.1707679

Avraamidou, L. (2020). Science identity as a landscape of becoming: Rethinking recognition and emotions through an intersectionality lens. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 15(2), 323–345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-019-09954-7

Cohen, E. G., & Lotan, R. A. (2014). Designing Groupwork: Strategies for the Heterogenous Classroom (3rd ed.). Teachers College Press.

Jackson, J., Dukerich, L., & Hestenes, D. (2008). Modeling Instruction: An effective model for science education. Science Educator, 17(1), 10–17. http://modeling.asu.edu

Kalender, Z. Y., Marshman, E., Schunn, C. D., Nokes-Malach, T. J., & Singh, C. (2019). Why female science, technology, engineering, and mathematics majors do not identify with physics: They do not think others see them that way. Physical Review Physics Education Research, 15(2), 020148. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevPhysEducRes.15.020148

Kim, A. Y., & Sinatra, G. M. (2018). Science identity development: an interactionist approach. International Journal of STEM Education, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-018-0149-9

Louie, N. L. (2018). Culture and ideology in mathematics teacher noticing. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 97(1), 55–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-017-9775-2

NGSS Lead States. (2013). Next Generation Science Standards.

O’Shea, K. (2012). Whiteboarding mistakes game: A guide. Physics! Blog!

O’Shea, K. (2016). Being “smart” in science class. Plysics! Blog! https://kellyoshea.blog/2016/11/08/being-smart-in-science-class/

Wang, J., & Hazari, Z. (2018). Promoting high school students’ physics identity through explicit and implicit recognition. Physical Review Physics Education Research, 14(2). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevPhysEducRes.14.020111

Wieselmann, J. R., Dare, E. A., Ring-Whalen, E. A., & Roehrig, G. H. (2019). “I just do what the boys tell me”: Exploring small group student interactions in an integrated STEM unit. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 57(1), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21587

Wildeboer, B. (n.d.). Student discourse question stems. Retrieved December 11, 2024, from https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1Wml9a25NV1Qv-73RnK_zLKE1zG3RQaJgsBX2UMf7XYc/edit#slide=id.p

Using Group Roles to Promote Collaboration

Posted by Marta R. Stoeckel in Uncategorized on December 22, 2024

This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in The Science Teacher on Nov. 21, 2024, available at https://doi.org/10.1080/00368555.2024.2404955

In classrooms implementing science education reforms such as those laid out in the Framework for K-12 Science Education (National Research Council, 2012), it is important for students to spend time working in groups, discussing their thinking, and building on each other’s ideas. Collaboration like this is a skill and students need support to learn to collaborate effectively (Cohen & Lotan, 2014). In this article, I will share how I use group roles as a tool to help students learn how to collaborate equitably and productively and to engage deeply with each others’ ideas.

Why use group roles

I started using group roles in my classroom not long after I started using a curriculum that relied heavily on small group work and student-to-student discussion. I initially found that a small number of students, mostly white boys, tended to take charge in their groups and to speak the most during discussions. As I started to look for ways to shift this pattern, I found social status was a useful way for me to think about this problem. Students unconsciously assign each other status based on factors including social savviness, race, gender, economic status, and many others that have very little to do with science (Cohen & Lotan, 2014). The status someone is seen to have has significant impacts on the ways that students interact during group work. For example, boys’ ideas tend to be taken more seriously than girls’ ideas in mixed-gender groups (Wieselmann et al., 2019), which I realized was happening in my classroom. In addition, the more unstructured an activity is, the more inequitable participation tends to be, which explains why this problem became so much more apparent in my classroom as I worked toward students driving the sense-making and engaging deeply in the science practices. I noticed that girls, especially girls of color, were less likely to be listened to by their peers or excluded from small group discussions during guided-inquiry activities than during more structured labs. Group roles can disrupt status by giving students some structure for their interaction without getting in the way of students’ responsibility for how they are doing the science. It is important to keep in mind that no one strategy is a guarantee of equitable, high-quality collaboration, so group roles are most effective when combined with other strategies to promote effective collaboration, such as those described in Cohen and Lotan’s Designing Groupwork: Strategies for Heterogeneous Classrooms (2014).

Types of roles

When students collaborate, they tend to either split tasks, with each person taking responsibility for some definite aspect of the larger task, or to share tasks, with students engaging directly with each others’ thinking to complete the task together (Doucette & Signh, 2022). Different types of roles can support these different types of collaboration. I call roles that support splitting task-oriented roles, since they usually describe the specific jobs that students will hold, such as timer, recorder, or materials gatherer. These types of roles are useful when students are doing something like a lab activity where several things need to happen at once. I avoid having fixed task-oriented roles that we use consistently in my classroom, instead discussing with students what smaller tasks are necessary for the day’s activity and tailoring the roles we will use to fit the activity. For example, one of the first labs students do in my class is constructing a position vs. time graph for a buggy moving at a constant velocity. During the whole-class discussion preceding the lab, we identify the tasks groups will need to complete and develop task-oriented roles. The exact roles vary, but typically include a role to release and catch the buggy, a role to mark the position of the buggy, and a role to run the timer. In their groups, students then decide who will take each role the class identified. As students get more adept at effective collaboration, I shift to having students determine with their group what roles they need. For example, when students do a lab to find variables that affect the period of a pendulum, they first write out the procedure they will use. Then, each group identifies the tasks they will need to split and come up with roles that usually include running the timer, releasing the pendulum, measuring release angle with a protractor, and recording data. Because collaborating by splitting tasks feels relatively natural to students (Doucette & Singh, 2022), I find students can begin taking responsibility for managing this type of collaboration relatively easily.

There are a few important considerations with task-oriented roles. First, status can influence what roles are assigned to which students, with gendered patterns being especially powerful. For example, in mixed-gender groups, students will often default to assigning a role like “recorder” to a girl while boys will take roles that involve manipulating equipment (Doucette et al., 2020). This is something I see frequently in my classroom, usually justified by saying the girls have better handwriting. One strategy I’ve used to address this is to share that observation with students, which is enough for some boys to volunteer to be the recorder and for some girls to push back when a peer suggests they be the recorder. Another strategy is assigning roles to students myself , but this gives students less opportunity to manage their collaboration, so I use it sparingly. I’ve had the most success disrupting those patterns and ensuring students see the recorder as an active participant when, during the whole-class discussion about roles, I suggest pairing recording with another task that involves manipulating equipment.

I also find relying too heavily on task-oriented roles encourages what I call “parallel play”, where students each complete their piece of the task with minimal interaction with each others’ thinking. For example, while working problems that include representing the same motion using different types of diagrams using task-oriented roles, I often see groups decide on roles where each person is responsible for one type of diagram. Not only does that mean each student only thinks about one type of diagram, but they don’t think about the connections between the different diagrams and there is minimal discussion about how students decided to draw the diagrams. This is a prime example of a finding from Doucette and Singh (2022) that students tend tolearn less science when they are splitting tasks instead of sharing since they are not challenged to explain or revise their thinking and are not engaging with a variety of perspectives about the task.

I call roles that focus on the way students share tasks process-oriented roles, since they describe different ways of interacting. These include roles like facilitator, summarizer, and, my favorite, skeptic. Process-oriented roles describe ways that students can draw out and respond to each others’ thinking. My students are often slower to complete tasks when they are using process-oriented roles, but have much richer conversations, which mirrors research that students tend to take more time, but learn the science more deeply when they are sharing tasks (Doucette & Singh, 2022). I tend to use these roles much more frequently than task-oriented roles since this is a more challenging type of collaboration for students, but one that I want to prioritize in my classroom. I adapted process-oriented roles from University of Minnesota Physics Education Research Group (2012) to develop the roles shown in Figure 1 all year so that students have repeated practice with the skills called for by each role. Students often come into my classroom unsure of what this kind of collaboration looks like in practice. Early in the year, their priority is often completing the task and approaches like splitting up a problem set and copying each others’ answers is a very efficient way to complete a problem set quickly. I students to prioritize understanding the task, so I need to get them to slow down and see the value in discussing their thinking. Process-oriented roles help students understand how to effectively respond to each other’s’ thinking, giving them a chance to see for themselves how that kind of interaction supports their learning. Experiencing this helps students see the value in meaningfully engaging with their peers’ thinking, showing them the time and effort required to develop and use these skills is worth it. The roles also ensure that every student holds some status within the group since each student is responsible for ensuring the group engages in a particular type of thinking. With time, students come to recognize that everyone in the class, regardless of race, gender, or other identity, has something meaningful to offer the group which makes them less likely to ignore, exclude, or dismiss a peer simply because they do not have high social status.

Figure 1: A set of group role cards

Regardless of which type of role I ask students to use, I am careful to avoid roles like “manager” that reinforce status. A student who is placed in a role that carries the connotation of being in charge is going to hold a lot of status in the group. I find that especially when the student in that role holds other identities that tend to be privileged in science classrooms, such a white boys, it becomes very easy for the student in that role to dominate the group, even when that is not their intention. When I used a manager role, some students would tell their peers what to do, rather than working collaboratively to figure it out. I also often saw the manager’s ideas given more weight than ideas proposed by other students, giving them significant influence over how the group approached the task. Avoiding roles that imply a hierarchy helps communicate to students that I see a high-functioning group as one where everyone is an equal contributor, thereby reducing how much students are attending to status within their groups.

Logistics

While group roles are a valuable tool, they are also challenging for students to use since they are another factor that students must pay attention to during group work. There are several strategies I use to help students get comfortable using roles to support their collaboration. First, I am very strategic about the first activity where I have students use group roles. I usually choose an activity a few days into the start of the school year, when students are starting to make sense of routines, procedures, and other aspects of how to be a student in my classroom. I also try to make sure the first activity where we use roles is one where students will be able to see the value of the roles. On the first day of class, I give students a very open-ended task to create a graph that models the motion of a buggy moving at a constant speed and do not use any roles or other structures for collaboration. This first lab is a chance for students to get used to the idea that they will be working in groups and discussing with their peers in my class without having to worry about how to manage the collaboration. As part of the debrief, we talk about how the collaboration went and how we can improve how students are working together. We next repeat the lab with a more well-defined goal of a position vs. time graph for the buggy and with task-oriented roles that we determined during a whole-class discussion. Even though most groups naturally use task-oriented roles in the first lab, students typically recognize that taking some time to discuss the roles helped them split the responsibilities more equitably and efficiently.

To introduce process-oriented roles, I choose an activity that will have a lot of sensemaking, such as when students are attempting to construct a model or working on applying something they learned in the lab. In those kinds of activities, students can immediately see how the roles are helping them draw out and respond to their peers’ thinking as well as how the roles ensure they have opportunities to share their own ideas. I also try to pick an activity where the science concepts students are working with are relatively accessible while still having some room for depth. When students don’t have to think as hard about the disciplinary core ideas, they can pay more attention to how they are interacting with their peers and what the group roles are asking of them. I introduce process-oriented roles when students are doing problems to practice translating between different representations of motion with a constant velocity, including position vs. time graphs, velocity vs. time graphs, verbal descriptions, and motion maps. The content is accessible enough that students can usually give some attention to their collaboration, but there is still enough challenge for them to have meaningful conversations about the problems, so they see the value of engaging with each other’s thinking. Just like many of the other skills we practice in science, as students gain experience with the group roles and the skills associated with each one, they need less attention to use those skills and can lean on them when the science is more challenging.

Another strategy I use is to give students cards that have sentence starters for each role, such as those in figure 1. This gives each student a physical artifact they can place in front of themselves as a reminder of what their role is. The sentence starters also help students understand what it means to engage in each of the roles and gives them a scaffold in engaging with their peers’ thinking. I very intentionally made most of my sentence starters questions. This disrupts status by showing students how they can contribute to their group even if they don’t know the answer. It also places explicit value on questions, an important science practice that students often undervalue since questions also mean showing ignorance. Many students have experienced negative reactions from peers when they ask questions and, for students with a marginalized identity, those reactions can include microaggressions. Early in the year, students can justify their questions as part of their role, even when it comes from genuine confusion. With time, students experience how valuable questions are and stop reacting negatively to their peers’ questions. I frequently get feedback that students feel safe asking questions in my class.

Once I introduce students to a set of process-oriented roles, I stick to those roles so that students can get comfortable with those roles and ways of engaging. I let students decide with their group how to assign roles the first time so that most students can take a role that plays to their strengths, which makes it easier to stick to the roles. Students are sometimes resistant to using roles since they associate them with younger grades, but letting students pick their roles can reduce this resistance by giving them some autonomy. After using the roles a few times, I start assigning roles randomly and discuss with students that this will help them expand their repertoire of ways to respond to others’ thinking. The cards provide a natural way for students to randomly select roles since they can simply place the cards face down and each pick one.

Typically, I use the roles at least once per week early in the year but use them less often as students get better at collaborating. My decisions are always a judgment call based on my observations of the class and what I see in student reflections on their collaboration. With time, students start using the skills associated with each role with less prompting and internalize the useful aspects of the roles. As a result, the roles become less necessary as a scaffold.

But kids don’t stick to their roles!

Other teachers consistently ask me how I make sure that students are sticking to their assigned roles. The short answer is, I don’t. The reality is there is no practical way for me to enforce students following roles, especially process-oriented roles. That doesn’t mean that roles don’t serve a purpose when students aren’t strictly following them. Whether or not students follow them, having roles sends a message that I believe everyone can and everyone should contribute to the group, which reduces the impact of status in groups. The roles also communicate what productive collaboration looks like and give students language for productive ways to engage with each other even when they are not using the roles. The first year I used group roles, an instructional coach observed me as students did a lab before I introduced roles and a few days later when students had roles. I was frustrated because students were not using the roles, but the coach pointed out their collaboration was much better when they had roles because of the clear expectation that everyone can and should contribute.

The roles are also available for students as a tool when they are stuck. On many occasions, I have seen a student who did not see the roles as valuable fill the awkward silence by making a show of picking up their role card and reading a sentence starter in a tone intended to mock the card , only to start a productive conversation that moved the group forward. I sometimes have groups ask for the role cards after I’ve phased them out because they are struggling and want a tool to help their group think the task through. By viewing the roles as a resource, rather than a requirement, I’ve been able to see it’s okay that students won’t always follow them.

Conclusion

Teaching students how to collaborate effectively and equitably is challenging, but necessary to implement science education reforms that call for students to share their thinking and engage with each other’s ideas. Group roles are one strategy for reducing the impact of status in how students interact and for teaching them what it looks like to work together effectively and equitably. In particular, using process-oriented roles can help students learn how to take their collaboration beyond splitting tasks and make meaning together.

References

Cohen, E. G., & Lotan, R. A. (2014). Designing groupwork: strategies for the heterogeneous classroom third edition. Teachers College Press.

Doucette, D., Clark, R., & Singh, C. (2020). Hermione and the secretary: How gendered task division in introductory physics labs can disrupt equitable learning. European Journal of Physics, 41(3), 035702.

Doucette, D., & Singh, C. (2022). Share it, don’t split it: Can equitable group work improve student outcomes? The Physics Teacher, 60(3), 166-168.

National Research Council. (2012). A Framework for K-12 Science Education: Practices, Crosscutting Concepts, and Core Ideas. National Academies Press.

Physics Education Research Group. (2012). Cooperative group problem solving. University of Minnesota. https://groups.physics.umn.edu/physed/Research/CGPS/CGPSintro.htm

Wieselmann, J. R., Dare, E. A., Ring‐Whalen, E. A., & Roehrig, G. H. (2019). “I just do what the boys tell me”: Exploring small group student interactions in an integrated STEM unit. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 57(1). https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21587

Problems and Potentials of Science Identity

Posted by Marta R. Stoeckel in Uncategorized on April 20, 2023

Recently, I presented my thesis proposal, which means I shared what I’d like to do for my dissertation with a faculty committee who gave me feedback. Science identity is a major theme in my work so far and my committee members raised two questions that I’ve been chewing on ever since:

- What do I find compelling or useful about science identity?

- What are my critiques of science identity as a framework?

As I move into the next phases of my dissertation, I wanted to do some journaling to delve into my current thinking on these questions and weigh their implications for my next steps. This post is admittedly much more navel gaze-y than I typically post since I am thinking about making sense of a theoretical construct, rather than about a challenge of classroom instruction.

I see a lot of discussion about science identity, in my work as a teacher, my work as a curriculum leader, and in my research as a PhD student. Programs like STEP UP and the work of scholars including Gholdy Muhammad have helped expose teachers to the language of identity. Teachers have taken up the framework identity in their classrooms in a variety of ways, including Kelly O’Shea’s lesson on values and beliefs about doing physics and Marianna Ruggerio’s identity encounters. The fact that what started as a scholarly theoretical framework has become such familiar language speaks to how much the concept resonates with educators. The seeming pervasiveness of science identity in my work means that considering my answers to the questions from my committee will not only inform how I move my dissertation forward, but have implications for my work as an educator.

I think part of what makes science identity compelling to me is the same thing that makes it so pervasive. Every year, I hear from student after student that they “just aren’t a science person.” The short definition of science identity is being seen by yourself and others as the kind of person who does science (Carlone & Johnson, 2007), which makes it a useful tool in unpacking what students mean when they make claims about whether they are a “science person”. Science identity is also a model with some predictive power since there is evidence it is a predictor of students’ intention to persist in a science discipline (Hazari et al., 2013).

This is a tempting place to stop thinking about identity, but this understanding lends itself to a deficit perspective. Girls, especially Black and Latina girls, are less likely than their peers to report a physics identity (Hazari et al., 2013), so the solution must be we have to convince girls they can be physics people, too, right? If we can just figure out how to inspire girls, then we can solve the problem of gender equity in science! A view of science identity that accepts this answer feels like a very individualistic way of understanding identity. It is something that individuals hold and we need to figure out how to fix people who are marginalized in science so that they can hold the correct identity. It is also a view that upholds the status quo by never questioning what about the ways students interact in science classrooms and beyond shapes whether students see themselves as science people.

I’m interested in a view of identity that is deeply relational. When students are in our classrooms, part of what they learn is what kind of person does science, whether they are capable of doing science, and whether their other identities are compatible with doing science (Brickhouse, 2001). This does not happen in isolation; it happens through interactions with peers and teachers. This is part of why I like Carlone and Johnson’s (2007) model of science identity, which includes competence, performance, and recognition. Competence is demonstrating skills or knowledge associated with science. Performance is behaving and interacting in ways associated with science. Recognition is being seen by yourself and others as a science person. The performance and recognition dimensions in particular make clear that if you are going to understand science identity, you need to understand how students interact and relate to each other in science classrooms. Hazari , Sadler, and Sonnert (2010) revised this framework to include a fourth dimension of interest. While I see the arguments for including interest and there are meaningful questions it helps answer, I haven’t found ways to use interest for thinking relationally about identity, so haven’t embraced this version.

Even with a more relational view of identity that includes tools to understand how identity emerges through interaction, there are still issues with science identity. I love Carlone’s (2003) question “When we ask students to participate in school science, what kinds of people are we asking them to become?” (p. 20). Whether we like it or not, students have ideas about what it means to be a science person, especially when it comes to the performance dimension. In one study middle school students said being a science person requires wearing goggles (Dare & Roehrig, 2016) and, in another study, even undergraduates majoring in science felt like they were not science people because they don’t own goggles or lab coats (Nealy & Orgill, 2019). Many of the performances that are part of a science identity are associated with whiteness and masculinity (Brickhouse, 2001), which means that asking marginalized students to become science people can mean asking them to leave behind other aspects of who they are.

But what if our goal wasn’t just to give students access to a science identity as it currently exists? Why can’t we design our classrooms to reshape and expand what students think it means to be a science person? I think part of that is making sure students are exposed to a wide range of scientists, not just the canon that portrays science as mostly white men (plus Marie Curie). But that is not enough. Ilana Horn has written about expanding what it means to be smart in math class and there is no reason we can’t do the same thing in science classrooms (Kelly O’Shea has written about her efforts to do just that). As I think about how to frame the research in my thesis and work on the framework I will use to connect identity to the other concepts I am working with, I think one piece will be shifting my reading to learn more about normative identity, which is the communal understanding students come to of what it means to be a particular kind of person (Cobb et al., 2009). What normative identity do students associate with a science person in my classroom and how do they arrive at that normative identity? How do students enforce that normative identity through interaction? And, most importantly to me, how can teachers reshape our classrooms to expand the normative identity of science person?

References

Brickhouse, N. W. (2001). Embodying science: A feminist perspective on learning. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 38(3), 282–295. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-2736(200103)38:3<282::AID-TEA1006>3.0.CO;2-0

Carlone, H.B. (2003). (Re)producing good science students: Girls’ participation in high school physics. Journal of Women and Minorities in Science and Engineering, 9(1), 17–34.

Cobb, P., Gresalfi, M., & Hodge, L. (2009). An interpretive scheme for analyzing the identities that students develop in mathematics classrooms. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 40(1), 40-68. https://doi.org/10.5951/jresematheduc.40.1.0040

Carlone, H. B., & Johnson, A. (2007). Understanding the science experiences of successful women of color: Science identity as an analytic lens. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 44(8), 1187–1218. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20237

Dare, E. A. & Roehrig, G. H. (2016). “If I had to do it, then I would”: Understanding early middle school students’ perceptions of physics and physics-related careers by gender. Physical Review Physics Education Research, 12(2), 20111–20117. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevPhysEducRes.12.020117

Hazari, Z., Sadler, P. M., & Sonnert, G. (2013). The science identity of college students: Exploring the intersection of gender, race, and ethnicity. Journal of College Science Teaching, 42(5), 82–91. https://doi.org/10.2307/43631586

Hazari, Z., Sonnert, G., Sadler, P. M., & Shanahan, M.-C. (2010). Connecting high school physics experiences, outcome expectations, physics identity, and physics career choice: A gender study. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 47(8), 978–1003. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20363

Nealy, S. & Orgill, M. (2019). Students’ perceptions of their science identity. Journal of Negro Education, 88(3), 249–268.

What does my research mean for my classroom

Posted by Marta R. Stoeckel in Uncategorized on August 24, 2021

In July, I published an article from my PhD research on the kinds of classroom experiences that my AP Physics 1 students saw as important to building confidence and self-efficacy. As I prepare to head back into the classroom next week, one of the things I’m thinking about is what I want to bring into my practice as a result of what I’ve learned from my research. I’m most focused on the qualitative parts of my study, where I collected students’ reflections on what helped them master the course content and interviewed a small group of students about what experiences they saw as contributing to or detrimental to their self-efficacy.

One of my takeaways is the start of the school year is critical to students’ perceptions of whether they are good at physics. I interviewed students in May, but every single student who mentioned a specific lesson or activity in their interview mentioned something from the first few weeks of school. While the memories students shared in the interviews were consistently positive, I’m thinking about how I can integrate building self-efficacy into my typical classroom culture setting. In Physics, I’ve done some post-activity discussions where students identify some of the skills their group needed to complete the task. After a conversation with Kelly O’Shea, I’m thinking about trying those discussions before activities to give students the expectation in advance that they will have useful skills. I also want to see if I can integrate personal reflection into these discussions to get students thinking not only about the skills the task required, but the skills they brought to their group.

I suspect this approach could also help with some of what students had to say about guided inquiry paradigm labs in my interviews. Students drew a lot of self-efficacy from the sense of ownership these labs gave them over their learning, but they also took negative messages about self-efficacy from the confusion and uncertainty that are what I consider an expected part of the process. I think part of this, especially in AP Physics, is my students often associate being good at physics with having the right answers. My hope is that taking class time to name other ways of being good at physics, especially if I have students do some personal reflection, will help students recognize the skills and effective strategies they are using to work through the confusion and uncertainty and those can become moments that contribute to students’ self-efficacy.

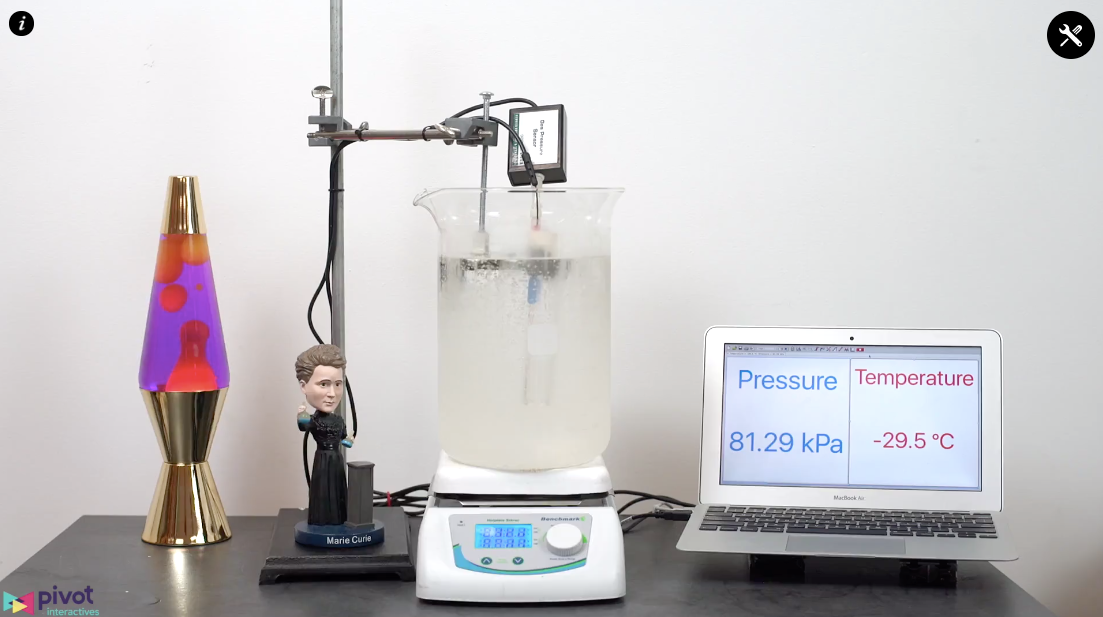

My students also had a lot to say about digital labs. Students told me that part of what helped them develop self-efficacy from labs was the experience of describing something they saw as part of the “real world”. They saw simulations and video-based labs as removed from that real world, which made them less valuable for self-efficacy. With that in mind, I want to try introducing digital labs with a hands-on experience or a phenomenon students are familiar with, then draw a clear link to the digital lab as a way to explore more deeply. Students also told me that feeling like they didn’t know how to use the tools in digital labs had a negative impact on their self-efficacy. That should be easy to address. No matter how simple or intuitive a digital tool seems to me, I need to make sure I provide students with instructions and resources on how to use the technology so that students can focus their attention on the science, instead.

Finally, one of the findings I was most excited about is that some of my students, especially girls, interpreted my feedback on assessments where they had low scores as evidence that I believe they can improve and are therefore good at physics. That is exactly the kind of message I want students to take from assessments with a low score and reinforces that I have lot of responsibility for cultivating a classroom climate where students develop have a growth mindset about physics. I think one important part is I assess every standard at least twice in my class, so when students have a low score, they know that they are guaranteed an opportunity to apply my feedback and show their growth. I started doing multiple in-class assessments to minimize retakes outside of the school day, but I think it also communicates that I believe students can and will improve, which makes me think it would be worth considering this assessment approach in Physics. I also want to get better at making that message explicit in both my courses.

As far as the feedback itself, the students I interviewed talked about two main features. First, they talked about how even when they did a problem wrong, I would point out good ideas or strategies they had. This helped students feel like they had a foundation to work toward mastery, so I want to be conscious this year of recognizing and commenting on those positives in students’ work. Students also responded to my habit of writing questions or suggesting they try a diagram, rather than just putting what they should have done, since that sent the message that I believe they can figure it out with a little nudging. I tend to give more specific, direct feedback about what students should have done at the beginning of the year as I figure out what kinds of questions work best with different students, but I think it will be worth focusing on questions and other nudges from the start so that students get growth messages from my feedback from their very first assessment.

Ultimately, my goal is to make my classroom a place where all of my students see who they are as compatible with being a science person. Part of that is cultivating a classroom climate where students recognize the ways they are good at physics and can develop confidence and self-efficacy. One of the privileges of having the time and resources to examine my classroom with a researcher lens is I can take a detailed look at my students’ experiences to better understand the ways I’m reaching and falling short of that goal.

Musings on Instructional Shifts

Posted by Marta R. Stoeckel in Uncategorized on June 17, 2021

This year, I took on the role of Secondary Science Standards Implementation TOSA, which is a fancy way of saying I’ve been working with the 6-12 science teachers to transition to a new set of state standards based on the NGSS. This week, I wrapped up my responsibilities for the year with a few days of curriculum writing with our 6th grade science teachers, who will implement the new standards in September. It has been fantastic listening to their conversations and seeing teachers who were wary of these shifts in November get excited about what their classrooms can look like in the fall. As I think about the grade levels that will begin their shift next fall, I’m reflecting on what I think have been some important factors in the success (so far) of the 6th grade team.

I am one of those progressive physics teachers that scoffs that textbooks are for propping up ramps and vastly underestimated the value in piloting a published curriculum. While I don’t use a traditional textbook, I am able to teach the way I do because I have access to materials like the Modeling Instruction curriculum and New Visions science materials, which were especially crucial early in my instructional shift. Those materials helped me visualize what student-centered instruction could look like in the classroom and served as a guide for how to help students develop skills in science practices and discourse. Based on the conversations this week, the published curriculum is filling a very similar role for the 6th grade team. The team even talked about some changes to the materials they are developing from scratch based on what they are learning about using phenomena and scaffolding science practices from the published curriculum.

Another important realization is how overwhelmed a lot of one-shot presentations have left many teachers feeling. A lot of local presentations have focused on what a big shift the new standards are and have left many teachers in my district with the misconception that they should be doing completely open inquiry all the time. Teachers have been very vocal that they appreciate the PD sessions I’ve planned that focus on the “guided” part of guided inquiry where we look at how to strategically constrain activities or steer discussions to keep the scope manageable and ensure students get to the target science content. What seems to work is I am not only showing them the shift, but giving them concrete tools to help make that shift. I’ve been worried about making sure some people recognize the magnitude of the gaps between what we do now and what we’re being asked to work toward, but I think is much more important for me to focus on making the gap feel navigable.

I think a key element next year will be ensuring the 6th grade team has ongoing support in the instructional shift. My district is one of many places where teachers have attended high-quality PD individually and come back excited to apply it in their classrooms, only to fall back on old curriculum and old habits once the school year starts and they are trying to make changes on their own. When I look back at my own shifts, I had a lot of days where I felt like I’d gotten worse as a teacher and the support systems I had were critical to sticking with the changes I was making. As part of the EngrTEAMS project, I had a graduate student coach who joined my classroom during an integrated STEM unit and had reflective coaching conversations with me about each lesson. Around the time I took my first modeling workshop, I started joining regular video chats with Kelly O’Shea, Michael Lerner, Casey Rutherford, and others where we talked through what was and wasn’t working in our classrooms. Both of these were a source of accountability to stick with changes and an opportunity to problem-solve when I had challenges, which were necessary in sticking with the changes I was making. The Teaching & Learning department is taking steps to protect time for the 6th grade science teachers to meet with each other partly so that they can be a source of mutual support. We’ve also started working with administrators and instructional coaches in the middle schools to help them understand what the 6th grade team is trying to do and start thinking about ways they can be supportive when teachers are struggling or frustrated. I also have a lot of flexibility to define what my role involves, and I think it will be worth carving out some time next year to facilitate conversations with the 6th grade team to talk through challenges. I think this is an area we often overlook with in-service teachers, but is crucial to making instructional changes sustainable and effective.

One advantage I’ve had this year is 6th grade science will be the only ones implementing the new standards in the fall, so I’ve been able to devote a lot of attention to that team. Next year, 7th grade, 9th grade, and 11th/12th grade physics will all be preparing to implement in fall 2022, so I will need to consider how to use my learning from this year and rely on the support of colleagues in certain roles to provide the same level of support to three different grade levels while also continuing to support the 6th grade teachers. I have a break from any formal responsibilities in this role until August, which gives me time this summer to continue reflecting on my work this year and planning how I will extend it in the fall.

Gender, Self-Assessment, and Classroom Experiences in AP Physics 1

Posted by Marta R. Stoeckel in Uncategorized on September 21, 2020

This post originally appeared as an article in The Physics Teacher:

Stoeckel, M. (2020). Gender, self-assessment, and classroom experiences in AP Physics 1. The Physics Teacher, 58, 399-401. https://doi.org/10.1119/10.0001836

One of the many ways issues of underrepresentation appears in the physics classroom is female students frequently have a lower perception of their performance and ability than their male peers1, 2, 3, 4. Understanding how classroom experiences impact students’ confidence, especially for underrepresented students, can provide an important guide to designing physics classrooms where every student sees themselves as capable of learning and doing physics. To explore these issues in my AP Physics 1 classroom, I started asking my students to self-assess as part of my assessment process, allowing me to collect data comparing students’ perceptions to their actual performance. I also conducted interviews and collected student reflections to gain insights into the classroom experiences that impacted students’ confidence in physics. My students made it clear that discovering concepts in the lab contributed to their confidence. Girls also built confidence from teacher feedback, even on assessments where they scored poorly, while boys saw peer interactions as a source of confidence.

Confidence & Why It Matters

Confidence describes a students’ perceptions with respect to actual achievement and is often a precursor to self-efficacy5. Self-efficacy refers to a students’ beliefs about their ability to achieve particular goals and is shaped by four major types of experiences: performance accomplishments, where the individual demonstrates mastery; vicarious experiences, where the individual watches someone they relate to demonstrate mastery; verbal persuasion, where someone else expresses their belief in the individual’s abilities; and emotional arousal, which describes the individual’s mental and emotional state during a task6.

Self-efficacy and confidence are important not only because they correlate with academic success6, but also because they appear to be connected to issues of underrepresentation in physics. Women in introductory physics courses tend to have much lower confidence than men1, 2, 3, 4. Marshman et al. also found that while the confidence of both men and women declined during an introductory physics course, the decline was much greater for women4, suggesting that understanding how classroom experiences impact confidence is an important piece of understanding issues of underrepresentation.

Quantitative Data Collection & Results

This study focuses on AP Physics 1 at a suburban high school. AP Physics 1 is a year-long elective taken almost exclusively by seniors. The curriculum for the course is loosely based on Modeling Instruction7. Typically, around 40 students per year, approximately 10% of a graduating class, enroll in AP Physics 1. 31% of the students in the course are girls, which is stark contrast to both the school’s non-AP physics course and to other Advanced Placement courses in the school, including AP Chemistry, where around 50% of the students are girls, suggesting there is an issue in the school unique to AP Physics 1.

In the course, students take assessments approximately once per week where they receive a score on a scale of 2 to 5 for each learning target assessed. At the end of each assessment, I ask students to predict their score for each learning target, then complete a short written reflection, as shown in figure 1. Over the course of two years, I recorded the scores students predicted, along with their actual scores for each learning target. I collected this data for a total of 92 students, 29 of which were girls.

I put these scores and self-assessments into a framework called the CCL Confidence Achievement Window5. This framework compares students’ confidence and actual achievement to sort them into four profiles: public, with high confidence and high achievement; underestimating, with low confidence and high achievement; unknown, with low confidence and low achievement; and overestimating, with high confidence and low achievement The public and unknown profiles are considered to have good calibration between students’ achievement and confidence, while the underestimating and overestimating profiles indicate poor calibration.

For each student, I calculated total actual scores and total self-assessment scores as a fraction of the possible points. I used the self-assessment values as a measure of confidence and the actual score values as a measure of achievement in order to plot each student onto a CCL Confidence Achievement Window5, as shown in figure 2. The majority of students had fairly good calibration between their self-assessment and actual scores, falling into the public and unknown profiles. In addition, boys and girls fell into each profile at similar rates, suggesting boys and girls in this classroom had similar degrees of overall confidence.

What Affected Confidence?

To understand how my students developed such a well-calibrated sense of their achievement, regardless of their gender, during the second year of data collection, I also recorded the responses students had to the open-ended prompt I included on the self-assessments, such as the one in figure 1, from the 52 students enrolled in the course that year. In addition, I interviewed ten student volunteers at the end of the second year about the experiences that affected their confidence. Three key themes emerged from the qualitative data: labs, peer interactions during whiteboarding, and assessment feedback.

Labs

On nearly every assessment reflection, students consistently mentioned labs as helping them achieve mastery, usually mentioning a specific lab done as part of the preceding unit, regardless of their gender. The interviews revealed what about the labs helped students develop their sense of confidence. In the Modeling7 approach, a new topic typically begins with a guided inquiry lab followed by a whole-class discussion of the results that allows students to develop conceptual and mathematical models for the new topic. The students I interviewed described this approach as giving them a sense of ownership of the material and showing them that they could discover new concepts, suggesting these labs were an opportunity for performance accomplishments, where students developed self-efficacy by demonstrating their own mastery of key skills6. As one girl put it:

“I think the self-discovery thing, like when you figure it out yourself, that’s always really good. Cause it makes you feel like you’re doing it yourself and you’re this scientist that knows everything.”

Students in the interviews also described making the transition from a lab to written problems as an important moment. Figuring out for themselves how to apply what they discovered in the lab to a new type of problem was another performance accomplishment That helped students see themselves as capable. In the words of one boy:

“I think when, not the lab, but after a lab that we do. So we do a lab that hammers at different the way that physics works and we get a problem set the day after. That it’s the same–they’re not the same thing, but it’s like the same concept. And then it’s like I semi-understand what we did yesterday and then we practice it and all the sudden, I just really understand the problems.”

Interestingly, during the interviews, several students also talked about labs as detrimental to their confidence; one boy even specifically described labs as having both a positive and negative effect on his confidence. Most students had minimal exposure to guided inquiry prior to AP Physics 1, resulting in some frustration for students. In interviews, students interpreted the confusion, mistakes, and other issues that are a normal part of guided inquiry as evidence they were not good at physics, especially if they had done well in previous science courses. This suggests it is critical to foster a classroom culture that normalizes confusion as part of the learning process to maintain the positive impact of labs on confidence.

Whiteboarding & Peer Interactions

The other major activity students mentioned on their self-assessments was whiteboarding, where students work in small groups to prepare a whiteboard with the solution to a problem which is then presented to the class. For boys, these activities were also an opportunity to build self-efficacy through verbal persuasion6. In the interviews, several boys brought up peer responses to their input during these activities, typically recalling specific problems and exchanges, often from several months prior, suggesting peer interactions had a lasting impact on students.

By contrast, while girls also said whiteboarding helped them master the content, only one girl spoke about peer interactions during the interviews. She recalled a specific exchange, in which her all-male group responded positively to her input, but she interpreted it as evidence she was fooling her peers, rather than an affirmation of her abilities:

“I think it’s one of those things where I’m generally a smart person, so they’d just assume that I kinda know what I’m doing, but they’re all super good at physics so I think they overestimate my abilities almost.”

This raises the question of what contributed to the very different recollections of peer interactions. Did boys have more interactions than girls where peers affirmed their abilities, or did girls have other experiences that lead them to view those interactions with a greater distrust?

Assessment Feedback

During the interviews, both boys and girls talked about in-class assessments, especially when I asked whether they think I believe they are good at physics. Most of the boys brought up specific assessments where they earned high scores as evidence of their physics ability. However, the girls talked about assessments very differently. Rather than talking about assessments where they had done well, the girls tended to talk about assessments where they had done poorly. The girls saw the kind of feedback I wrote on their assessments, along with a course policy encouraging retakes, as evidence that I saw them as capable of mastering the material, regardless of their initial score. As one girl put it:

“[You] offer constructive criticism when needed and it’s really helpful when trying to understand what I did incorrectly on quizzes and labs. So I believe that feedback really shows that [you] believe that I can do the course.”

For these girls, verbal persuasion in the form of my feedback did not have to be paired with a performance accomplishment to have a positive impact on their confidence.

Conclusions

Confidence is shaped by students’ experiences in the classroom, and understanding those experiences is particularly important for addressing issues of underrepresentation. In this study, students saw discovering a new concept in the lab and figuring out how to apply it to problems as particularly important opportunities for performance accomplishment, with girls in particular reporting less confidence on topics where they had fewer of these opportunities. Students of both genders responded to verbal persuasion, though boys focused on peer interactions and girls focused on teacher feedback, especially on assessments where they performed poorly. Designing a classroom where all students have the opportunity to develop a sense of confidence and self-efficacy means ensuring that all students have access to these kinds of experiences. It also means listening to students to better understand not only the kind of activities but the critical elements of activities that enable students to see themselves as good at physics.

References

- Emily M. Marshman, Z. Yasmin Kalender, Timothy Nokes-Malach, Christian Schunn, & Chandralekha Singh, “Female students with A’s have similar physics self-efficacy as male students with C’s in introductory courses: A cause for alarm?” Phys. Rev. Phys. Ed. Res., 14, 020123 (December 2018)

- Tamjid Mujtaba, & Michael J. Reiss, “Inequality in experiences of physics education: Secondary school girls’ and boys’ perceptions of their physics education and intentions to continue with physics after the age of 16,” International Journal of Science Education, 35, 1824-1845 (July 2013)

- Jayson M. Nissen & Jonathan T. Shemwell, “Gender, experience, and self-efficacy in introductory physics,” Phys. Rev. Phys. Ed. Res., 12, 020105 (August 2016)

- Emily M. Marshman, Z. Yasmin Kalender, Christian Schunn, Timothy Nokes-Malach, & Chandralekha Singh, “A longitudinal analysis of students’ motivational characteristics in introductory physics courses: Gender differences,” Canadian Journal of Physics, 96, 391-405 (May 2017)

- Lesa M. Covington Clarkson, Quintin U. Love, & Forster D. Ntow, “How confidence relates to mathematics achievement: A new framework,” Mathematics Education and Life at Times of Crisis, 441-451 (April 2017)

- Albert Bandura, “Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change,” Psychological Review, 84, 191-215 (January 1977)

- Jane Jackson, Larry Dukerich, & David Hestenes, “Modeling instruction: An effective model for science education,” Science Educator, 17, 10-17 (Spring 2008)

Self-Assessment & Underrepresentation in AP Physics 1 (NARST 2020 Presentation)

Posted by Marta R. Stoeckel in Uncategorized on March 24, 2020

Getting Students On Board with Active Engagement

Posted by Marta R. Stoeckel in Uncategorized on November 16, 2019

Over the past few weeks, I keep finding myself in conversations about navigating pushback from students and parents when using student-centered, active-engagement instruction, such as Modeling Instruction. Brian Frank tweeted a thread this fall on the fact that that while the frustration and misery that lead to pushback are common, they aren’t inevitable.

This paper https://t.co/zN4z0fYIUr is making the rounds, and so I’ll repost some comments I made on Facebook:

“So, I do believe it’s all very complicated and that it pulling it off is always a delicate matter…

— Brian Frank (@brianwfrank) September 6, 2019

When I used a more teacher-centered, traditional approach, building relationships with my students was enough to make kids comfortable in my classroom. But, when I started using Modeling Instruction, I found myself dealing with angry students, fielding phone calls and e-mails from frustrated parents, and even meeting with administrators when a few parents escalated upstairs. I eventually figured out the point Brian made in his thread–that you can reduce the misery by planning the right kind of classroom environment. While I certainly haven’t eliminated my students’ frustration, I now find my students are mostly onboard with the instructional approach I use and there are some particular steps that have been especially impactful.

Keep Students’ Perspective in Mind